It’s purely economic: SJ’s housing subsidies can’t benefit local homebuyers

While New Jersey is yet again subsidizing Tesla purchases, local Californian governments like SJ’s are footing the bill for further “affordable” housing development (though for taxpayers, these units are anything but cost-effective). Political economy professor Anthony Gill elaborates on why subsidies lead to market shortages and price increases that only benefit the sellers—and politicians, who “rake in the voter support from specialized interests.” To receive daily updates of new Opp Now stories, click here.

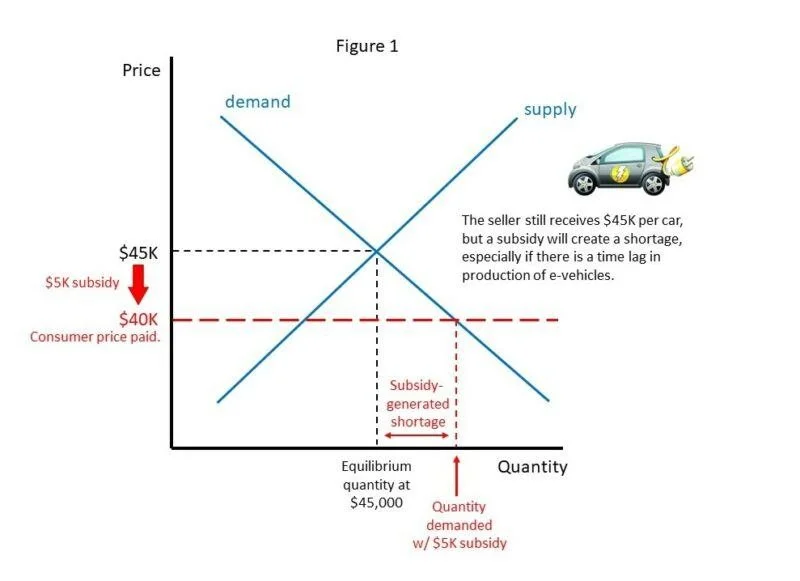

To illustrate, and to make the math easy, let us assume that the price of an average electric vehicle is $45,000. In a free market, this price is determined by supply and demand, with car companies setting the equilibrium price and quantity based on their manufacturing costs and consumer demand. So far, so good. This is standard Econ 101.

If a subsidy of $5,000 per car is offered to consumers, their effective price drops to $40,000 (see Figure 1). Not surprisingly, demand increases. Those individuals who previously had a maximum price of $40,000 at which they were willing to buy an e-car will now head down to their dealer with a government check for five grand in hand. On the supply side, auto sellers still receive $45,000.

But remember, prior to the subsidy program there were still individuals who were willing to buy the car for more than $40,000. All those individuals will have the gains from trade shifted in their favor. The person who was planning to buy an e-vehicle at $45,000 can now get it at $40,000, capturing $5,000 in consumer surplus.

Alas, if the auto company cannot manufacture cars quickly enough to satisfy the rush of new buyers who would be willing to spend $40,000, a shortage will result, representing the difference in the quantity of individuals willing to buy the current supply at $45,000 and $40,000 (see Figure 1). (While a shortage is typically measured by the difference between quantity supplied and demanded at any given price level, remember that the dealer will still receive $45,000 per car while the consumer only pays $40,000, with the remaining $5,000 covered by the government subsidy. That is why Figure 1 shows the shortage between the $45,000 equilibrium price and the quantity demanded at subsidized price of $40,000.)

As we also know from Econ 101, the easiest method of allocating scarce goods is to use the price mechanism. Seeing more people wanting the limited number of cars available, the rational response of the dealer is to increase the price of the vehicle back to the point where the quantity demanded meets the quantity of the current inventory. This is easily done by raising the price of e-vehicles by the price of the subsidy (see Figure 2)…

This article originally appeared in AIER. Read the whole thing here.

Follow Opportunity Now on Twitter @svopportunity